It has been an AGE since I last updated this project blog. Prepare for a long update.

Luckily, much has happened! I finished my first year of graduate school, but I also made some breakthroughs with the Dunlaps. Just to recap, in the last episode I was trying to piece together the deed path of 1298 Market Street through the online Grantor-Grantee Indexes for Beaver County. I had pulled together census records, death certificates, and any other documentation I could find on the Dunlaps and Mary Lena Keller, but information on the property remained stubbornly out of reach.

Well, then I went back to Beaver County this past March.

Access to the Recorder of Deeds Office at last! The very nice employees at the Office got me all set up and I spent four consecutive hours flipping through the big red books full of handwritten deeds with great success. I was able to trace the property that would become 1298 Market Street all the way from 1 April 1796 (when it was still part of a large parcel of land called Lot 39) up to the demolition of the mansion in 2017. Over the course of 221 years, that specific bit of property passed through only fifteen different parties (though it admittedly started as a very large parcel of land that was then subsequently broken into multiple pieces).

However, I was still not able to find written confirmation of when the house this whole project revolves around was actually built. I can make a few educated guesses, though. Let’s start on 4 October 1847, when Outlot 39 (the larger precursor to 1298 Market Street) and parts of outlots 38, 40, and 41 were conveyed by James W. Hempfield and his wife, Mary, to William Davidson for $3,000. Davidson then resurveyed the property and the lot numbers changed to the those they would retain to the modern day. The mansion sat on lots 7, 8, and 9, though the whole parcel of land Davidson held included lots 4, 5, and 6 adjoining, as well as lots 16, 17, and 18 on the opposite side of Market Street.

On 30 January 1841, lots 4-9 were conveyed by William Davidson and his wife, Margaret, to Andrew Purdy for $1,200. The mansion property is described as follows:

Lots 7, 8, and 9 adjoining, beginning at East side of Market Street and South side of Poplar Street, running by Poplar Street 163 feet to Walnut Alley, thence from Walnut 150 feet to Plum Alley, thence by Plum 156 feet to Market Street, along Market Street 150 feet to Plum Alley

Beaver County, Pennsylvania, Deed Book T: 315

Purdy also purchased lots 16-18 across the street. You may remember from my last Dunlap update that Andrew died and his wife, Almira, remarried to James Sholes [Shoals]. The Sholes then sold lots 4-9 and lots 16-18 to James Arbuckle for $3,000 on 31 March 1860. However, James Arbuckle then sold those same lots (4-9 and 16-18) to Samuel R. Dunlap for $6,000 only five years later. Now, the common story told about the Dunlap Mansion was that it was built in the 1840s, or that it was simply built by James Arbuckle. Based on the deeds alone (I didn’t quite have the time to get into the tax records) and the fact that the Greek Revival aesthetic stretched from the 1840s until approximately the 1870s, I surmise that Arbuckle did build the house, but it wasn’t until the 1860s. This isn’t to say that no structures existed on the property until the mansion, only that the house that was demolished in 2017 was actually constructed between 1860 and 1865.

After Samuel got ahold of the house and property, it stayed in the Dunlap family until 1924. I was so glad to find the following information, considering it never appeared in the indexes. I found out that Samuel conveyed the property to his oldest son, Joseph Hemphill Dunlap, in 1883. Then, prior to his death in 1909, Joseph (unmarried) conveyed the property to his remaining siblings: Ellen C., Anna C., and William B. Dunlap. The siblings sold lots 16-18, Ellen C. died unmarried in January 1913, and then William B. died unmarried in April 1922. From there the property passed to Anna. Here it’s important to mention that previously deceased sibling, Emma C. Dunlap Moore had a daughter, Mary Moore, who apparently lived in Ohio. As such, prior to her death in 1924, Anna C. Dunlap conveyed lots 4-9 “in consideration of One Dollar and love affection” to “Mary E. Moore, of city of Newark, County Licking, State of Ohio” and “Lena Keller, Bridgewater, County of Beaver, State of Pennsylvania” [Vol. 334: 26].

I lost track of Mary Moore between 1924 and 1946, but finally! I have the path mostly nailed down!

Now let’s talk reconstruction.

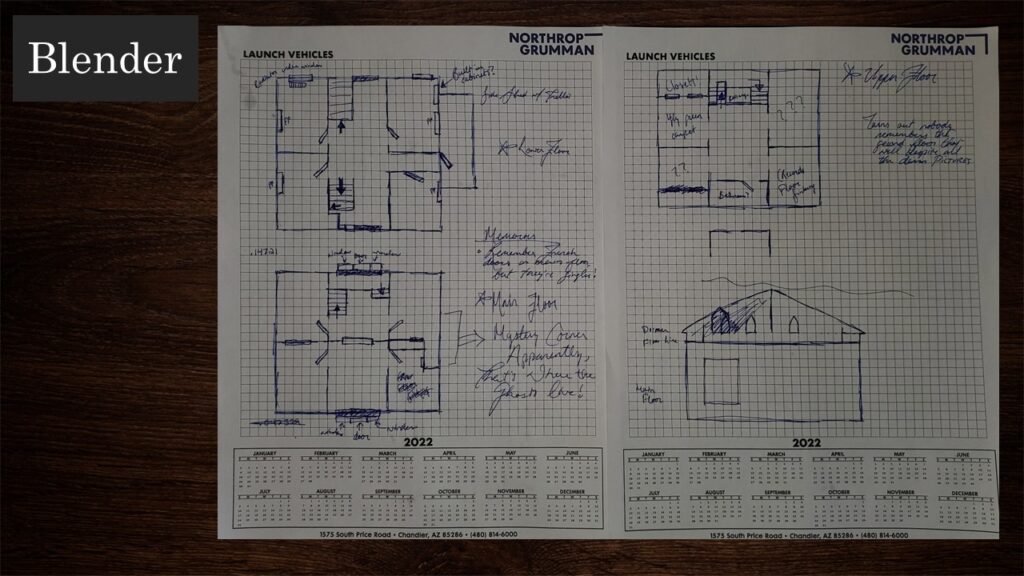

The whole goal of this project was to, basically, digitally reconstruct the Dunlap Mansion so that it can be explored in an entirely digital environment. As much fun as it’s been to nail down the actual history of a house I’ve only heard town rumors about, it was time to get to work on the actual meat of this project. To start, I needed a rough idea of how big the house was. Instead of trusting my eighth grade memories of how tall the ceilings were (though admittedly I have not exactly grown taller since eighth grade…), I turned to the application to add the house to the National Register of Historic Places and Google Earth. Now, Google Earth has a very handy measurement tool that I could use to get approximate length and width of the house. Piece of cake. But what about the height? In the application, it’s written that “The porches are formed by four massive columns, each measuring thirteen feet high and forty-eight inches in circumference at their widest point, tapering to the top.” With that thirteen-foot measurement, I could then pull a rough estimate of ceiling height just by looking at photos of the house. I very professionally did all this math on three sticky notes that then lived on my desk for weeks:

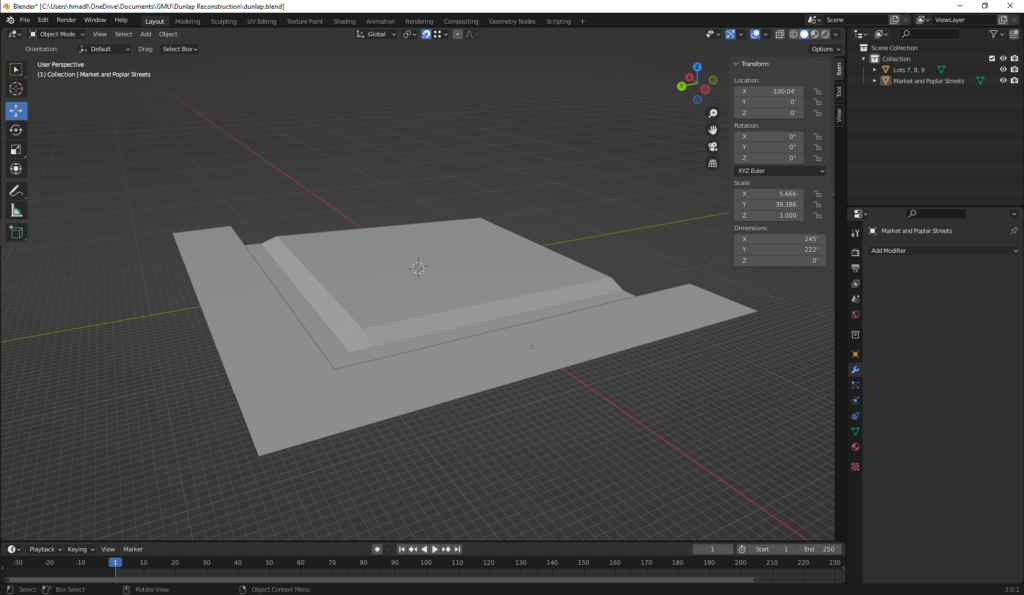

With these rough (and I mean rough) measurements in hand, I could dive into Blender.

For anyone who doesn’t know, Blender is a free open-source 3D modeling software that I picked up with the intention of using it for this project. There’s a pretty hefty learning curve, but it’s worked out pretty well so far. But even though I now had the measurements and the tools, I still had a major problem.

I couldn’t really remember the layout of the house.

There are some pieces that stick out in my memory, like the front rooms on the main floor and the one with ugly green carpet on the second floor. But I had personally never been down to the partially subterranean lower floor (let alone the actual cellar), and portions of the main and upper floors were fuzzy in my memory. And that’s where this project began to take on a different tone. Though I initially started this with the intention of historically reproducing the house circa its demolition in 2017, I realized that what I was actually going to create was going to be far from exact. Rather, I am essentially going to attempt to digitally solidify a memory of the house in a digital medium. Moreover, it wasn’t going to be just my memory of the house.

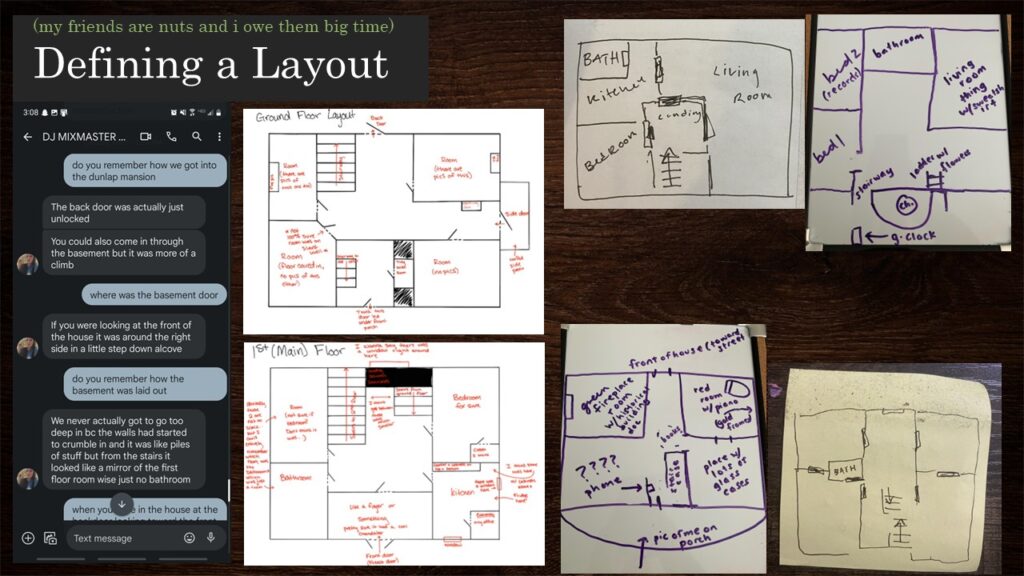

I reached out to friends who had also personally seen the inside of the Dunlap Mansion to help fill in the gaps in my memory. Interestingly, no one could remember the exact layout of the house, but we remember where objects in the house were. We essentially redrew the house based on where we remembered objects being, like rotary phones, records, and, yes, ugly green carpet. We remembered colors of rooms and fake flowers, but not where walls and doorways were. We remembered where we picked things up, but not how we got to those spaces in the first place.

Even so, my friends offered to draw what they remembered of the layouts. Within these layouts, those objects we remembered are placed in a 2D floor map of each story as we remembered it, but a few spots remained pretty fuzzy.

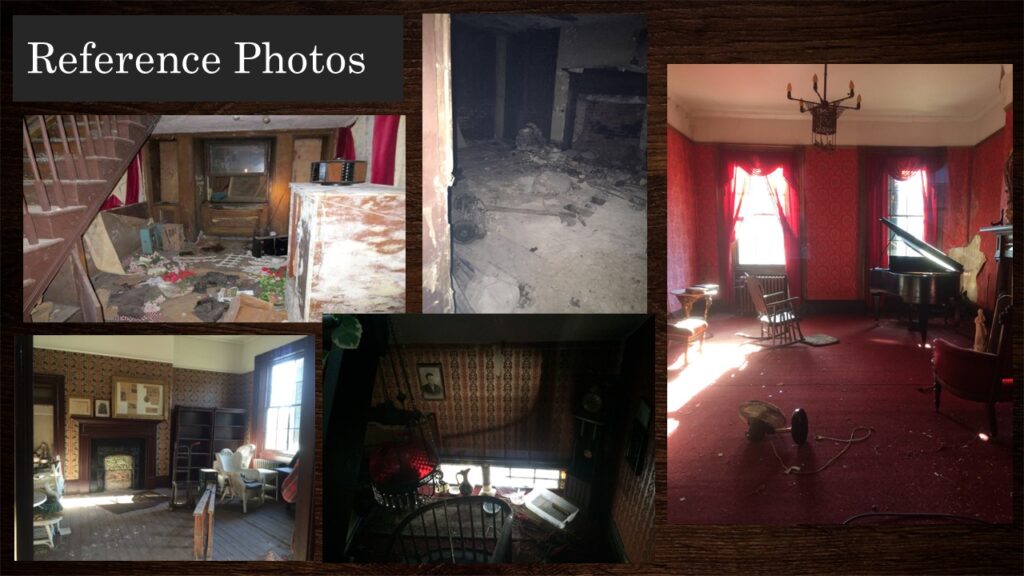

The funny thing about memory is all the contradictions it produces. I personally remember a bathroom on the main floor (mostly because it had a mirror and fashion plates of ladies in dresses on the walls). But others remember a closet with a tiny desk in it, or even a hallway. For some of these things we have photos essentially confirming their existence (though most of the pictures were, again, of objects because all teenagers are secretly magpies and crows in disguise and love shiny things). But for others, I am essentially going off of what everyone remembers and doing my best to condense it into some visual average of the space.

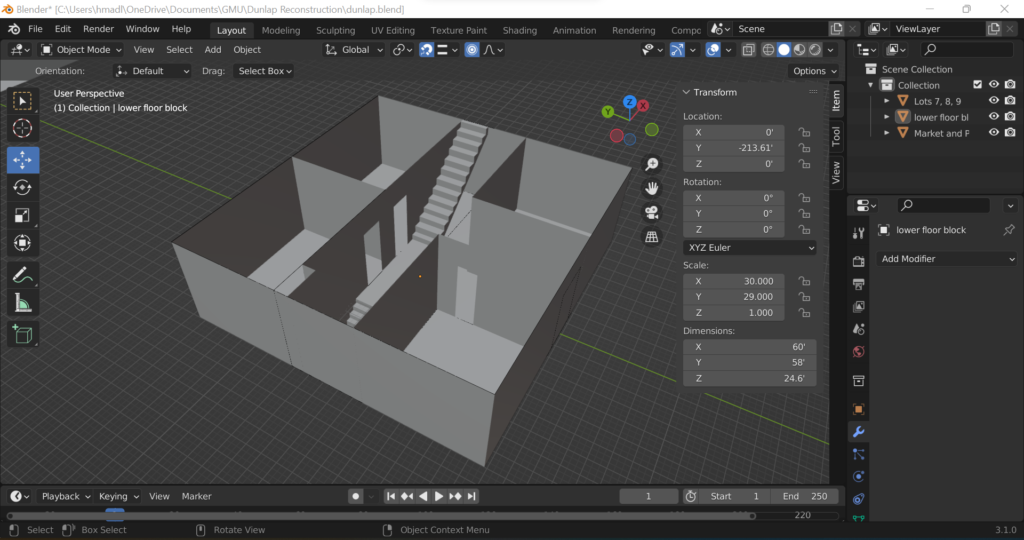

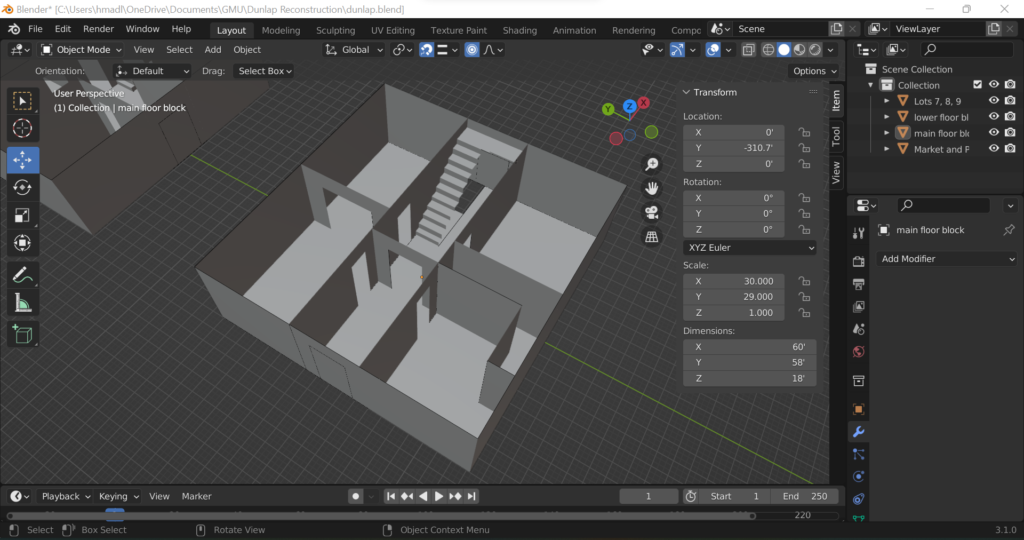

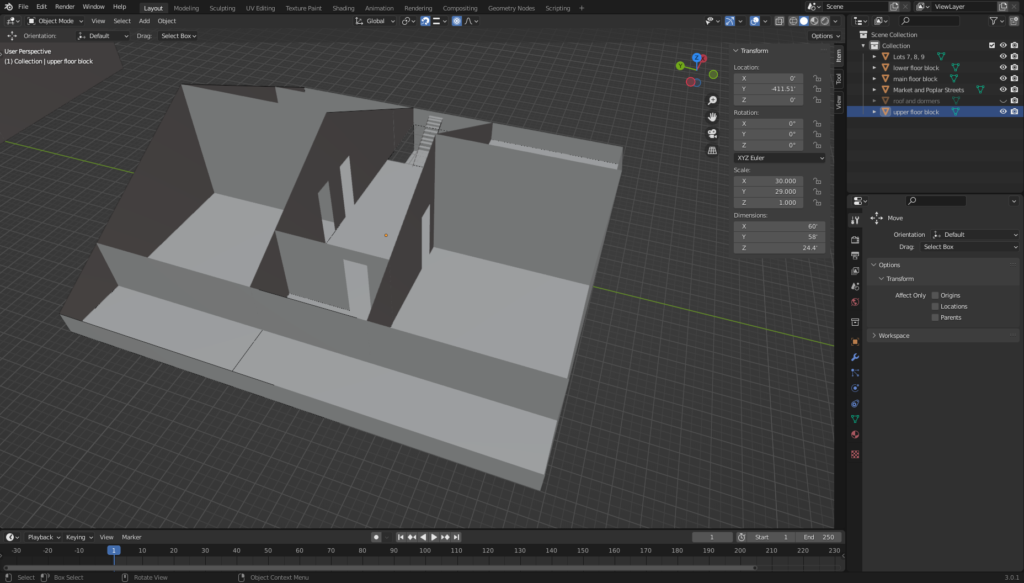

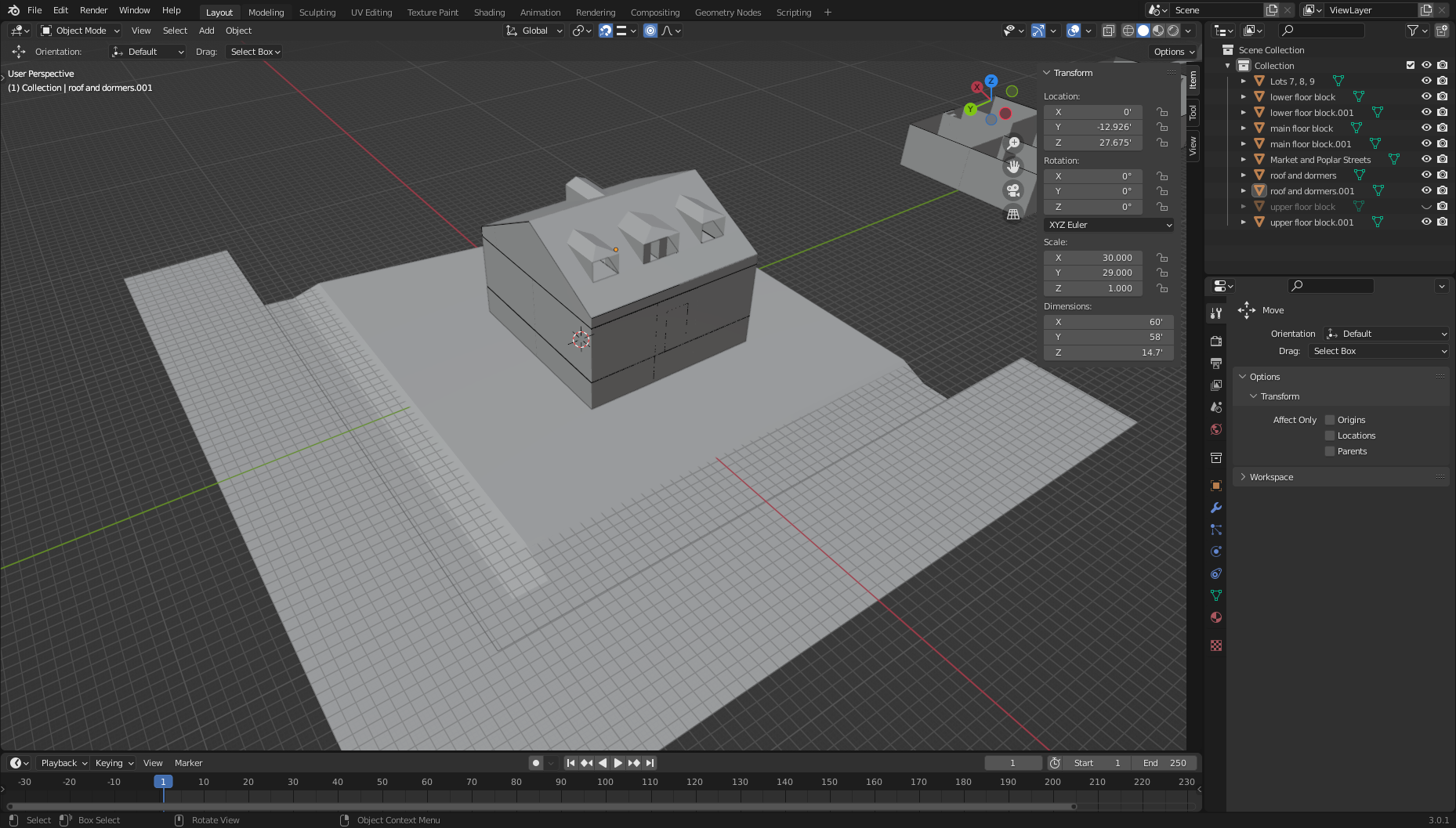

From here, I could block out a rough layout of the house in Blender. I decided to go with four “stories,” essentially: lots 7-9 themselves, along with Market and Poplar Streets; the lower floor, including the steps to the cellar; the main floor; and the upper floor. The following screenshots are far from the final rendering of the digital environment, but they exist as a guide for when I go to actually model the final product.

See for yourself how the lower floor moves within the 3D space of the application:

With the roof and placed where it would sit on the lots themselves, this is the full block:

Now you may have noticed that I did not block either of the porches. This is because the porches are the only things I’m certain I know exactly how they looked. I have multiple photos from multiple angles of both front and back porch, both from the 1890s and 2009-2013. Moreover, as I was constructing the blocks floor by floor, I didn’t want to mess with scaling the porches to fit the blocks exactly, as the porches and their roofs spanned multiple stories. I also chose not to block out windows, doors, or chimneys, again for similar reasons as the porches. Though these things will, of course, be in the final model.

Working in Blender has been a journey, and finding a way to visually represent something so abstract and amorphous as memory has grown into such an interesting challenge. In saying that, I have a few major goals to reach moving forward. First and foremost, I want to fully model each floor, the surrounding lot, and all other accoutrements. This will be done in Blender itself. After that, I plan to build an exploratory environment of the finished model using the free game engine Unity (or something similar). This will allow people to digitally explore the model itself and experience the memory-house in a video game like format. Lastly, the ultimate goal of this project is to evaluate this methodology for visualizing space and memory for future applications. I have high hopes for applying digital reconstruction to place, especially lost places. Just doing this small practice project has brought forth interesting revelations in how we remember space and how we apply our individual personalities and experiences to remembering that space.

I could keep going on the applications of memory and digital reconstruction, but this post is growing rather long. So I will leave this here, and say stay tuned for further updates!

Awesome job magpie!

Oh Hayley WOW! Very interesting detective work! Are you keeping track of hours spent on this?

Amazing update!!!! I’m glad your crow instincts are coming in handy.